Part 3: Properly Assessing a Threat and Analyzing its Risk

While the terms ‘threat assessment’ and ‘risk analysis’ have been frequently used interchangeably, they are not the same.

Threat assessment is focused on determining what the associated potential harm could be (how could it hurt me?). Threat assessment focuses on possible consequences vs. probable consequences. When completed, a threat assessment will contribute directly to a risk analysis by identifying the consequences that will drive the related vulnerability analysis.

Risk analysis is focused on the effect of an event or incident on specific objectives or activities. Risk is recognized as a factor of probability (will it happen?) and vulnerability (can it hurt me? / do I care?). Effective risk analysis requires an understanding of what the likely consequences of an incident or event are, and the impact of those consequences on your organization’s ability to function. The best risk analysis that I have seen or participated in have two levels to their analysis – the overall probability and vulnerability to a specific threat, and then additional analysis of likelihood and vulnerability to focused consequences related to that threat.

Who Should Be Involved In This Process?

The cliché is that it takes a village to raise a child. Well, it takes a team to accurately assess a threat. Applying a multi-disciplinary approach towards threat assessment and risk analysis is perhaps the single most crucial feature of a practical threat assessment and risk analysis. A threat assessment team will provide the analysis that an organization requires to effectively quantify and prioritize the threats that they face. A well-rounded team includes a versatile group that can bring a variety of perspectives, capabilities, and backgrounds to play.

Threat assessment and risk analysis depend on the synthesis and analysis of both administrative and operational points of view. The assessment team should be comprised of staff that possesses fundamental knowledge across the range of functional disciplines and departments within the organization. They should be experienced individuals who can understand the possible cascading impacts associated with a threat and their potential consequences.

The Threat Assessment and Risk Analysis Process

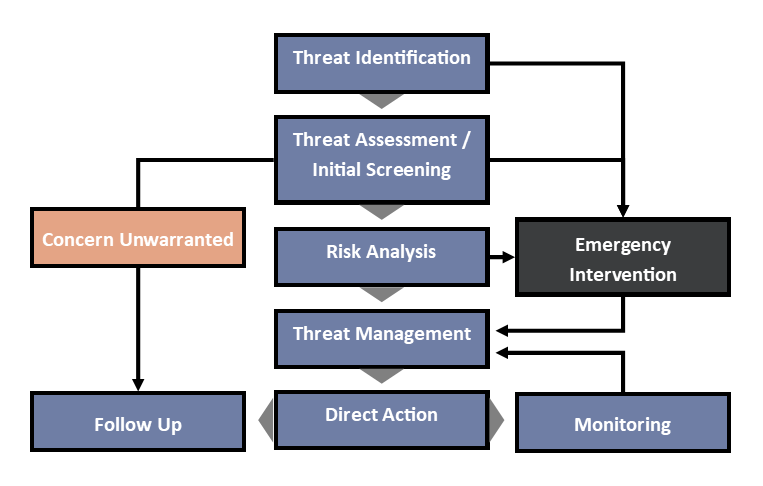

Because of the foundational role that threat assessment plays in a threat management program, I strongly recommend the use of a standardized approach across an organization. There are any number of focused threat assessment models out there. I use one based on best practices introduced by ASIS, the Association of Threat Assessment Professionals (ATAP), and the National Behavioral Intervention Team Association (NaBITA):

Threat Assessment / Initial Screening

Threat assessment is accomplished through a process of compiling and analyzing information about a threat to quantify the associated potential for harm. This boils down to determining what the possible consequences of an incident or event could be and identifying how those consequences may be mitigated. When dealing with human-centered threats, this involves consideration of interest, motive, and intention driving the potentially harmful action. For natural or technological threats, where there is no discernable intent involved, the focus is solely on the potential for disruption or level of lethality, which may result from an identified threat.

The goal of the initial threat assessment is to ascertain in a gross or general manner the urgency presented by the threat. The assessment team should consider all information available with the intent to determine if the threat is valid, a risk analysis is appropriate, or if emergency intervention is required. There are no standards for deciding which path to follow. The decision is based on the culture and tolerance for risk in an organization.

The Threat Assessment Process

Threat assessment involves an investigation into the identified threats, which consists of:

- Gathering information regarding the threats;

- Analyzing that information within the context of the organization; and

- Generating a list of possible impacts on the organization which the threat may inflict.

The assessment begins with seeking and collecting information to identify possible consequences associated with a threat. While the direct effects may be easily identified, a valid assessment looks at cascading impacts—secondary and tertiary disruptions, which may threaten an organization’s capability or capacity to operate. Once an understanding of the possible consequences associated with a threat has been established, an analysis should be undertaken to determine how those consequences could directly or indirectly impact the organization.

There are a variety of evaluation frameworks or models, rubrics, and analytic tools that can be used in this initial threat assessment, depending on the type of threat in question (violence, cyberattack, severe weather, theft, etc.) and customized to an organization’s threat criteria and tolerance. These tools should be used to initially assess, and then regularly reassess, the possible harm associated with a threat and determine if more in-depth risk analysis is warranted.

A standardized tool should be applied to objectively assess identified threats, regardless of how serious or trivial the threat may seem, and consistently use a rating system to indicate whether a threat is a low / medium / or high priority within an organization. Assessing the level of concern in this manner will enable the organization to identify its concerns and contribute directly to the vulnerability elements of a risk analysis process. I recommend that organizations document the determined priority level each time a threat is assessed, with the level potentially shifting over time as the environment evolves.

When the Assessment Reveals that Concern is Unwarranted

If based on the initial assessment, it is determined that concern regarding an identified threat is unwarranted, then no additional action may be necessary. That does not necessarily mean that the attitude toward the threat will not evolve or that environmental conditions will not change, resulting in a different assessment outcome in the future. If the assessment team determines that concern is unwarranted, then that decision should be recorded and revisited on a regular (at least annual) basis for reassessment.

When the Assessment Reveals that Emergency Intervention is Required

If the assessment team determines that emergency intervention is required based on the initial screening, then immediate action should be taken by the organization. In cases involving natural or technological threats, direct action may include the evacuation of personnel, deactivation of systems or networks, or other measures necessary to rapidly mitigate the potential for harm that was identified. For a human-centered threat, that action may involve a request for assistance from first responders or law enforcement, or activation of an organization’s focused incident response plan.

Conducting the Risk Analysis

Up to this point, we have solely been thinking about threat in terms of what is possible. Risk analysis brings probability into the discussion. As with a threat assessment, risk analysis should be conducted by a multi-disciplinary team using a standardized approach. While I can share best practices that I have found to be helpful, every organization needs to determine its own appetite for risk.

Traditionally, risk is defined as the probability of an incident occurring multiplied by the vulnerability of an organization to the harm associated with the threat being assessed.

Risk = Probability x Vulnerability

In most cases, that approach will provide an adequate level of awareness of the associated risk—and it can easily be visualized and provided to your team on a simple risk chart. Let’s evaluate each of these factors.

Evaluating Probability

Probability is the likelihood of something happening. Where base probability is usually expressed as a percentage, getting that detailed for a risk analysis does not necessarily provide additional value and a debate over a single percentage point for a probability score can quickly derail your entire threat assessment process. I recommend using a simplified five-point scale:

| Score | Probability Range | Description |

| Very Low (1) | 1 in 100 | Happens every 100 years (Catastrophic Flooding / Structural Collapse) |

| Low (2) | 1 in 10 | Happens every 10 years (Earthquake / Solar Flare) |

| Medium (3) | 1 in 5 | Happens every year (Tornado / Burglary) |

| High (4) | 1 in 2 | Happens every month (Lightning Strike / Robbery) |

| Very High (5) | ≥ 1 in 2 | Happens every week (Thunderstorm / Cyberattack) |

Evaluating Vulnerability

Vulnerability is a consideration of how badly a threat can harm an organization. Like probability, a five-point scale should provide an adequate level of detail to support risk analysis.

| Score | Level of Harm | Description |

| Very Low (1) | Negligible | Will not impact operations (Laptop Failure With Backup) |

| Low (2) | Minor | Disruption measured in hours (Injury Requiring Medical Attention) |

| Medium (3) | Major | Disruption measured in days (Local Evacuation Due to Weather) |

| High (4) | Severe | Disruption measured in weeks (Wildfire) |

| Very High (5) | Catastrophic | Disruption measured in months or greater (Pandemic) |

Calculating your Risk Scores

Risk analysis is usually represented as a discrete risk score, computed by multiplying the probability and vulnerability values. If you had a risk that was identified as having a high probability (4) and medium vulnerability (3), it would result in a risk score of High (4) x Medium (3) = 12.

Using a standardized five-point scale for risk analysis allows for the risk scores to be further defined into categories such as Catastrophic, Serious, Moderate, and Low based on the calculated rating.

- Catastrophic ≥ 15

- Serious ≥ 10

- Medium ≥ 5

- Low ≤ 4

In cases where a threat can have multiple vulnerability scores (for different locations, or different operational units within an organization), there are two conventional methods to calculate a single risk score:

- Probability x Highest Vulnerability where only the highest vulnerability score is used to calculate the risk score.

- Probability x Average Vulnerability where the vulnerability scores are averaged before being multiplied with the probability score

Additional Dimensions of Risk

Traditional risk analysis is meant to provide insight into whether there is a need to mitigate a threat, or whether it can be tolerated by an organization without compromising operational capability or capacity. Simplifying risk as a factor of only two variables (probability and vulnerability) allows for rapid analysis and relatively easy discussion of the results. While this quick and easy approach can provide an adequate quantification of risk, it does not necessarily provide the depth of understanding that may be needed in order to come to conclusions that drive the best possible outcome for a threat management program.

The complexities of a modern threat environment, especially when considering technological and human-centered threats, may require consideration of additional dimensions of risk to provide a more granular understanding of a threat’s potential within an organization, focusing on the interaction of the threat with an operational concern. As I discussed in my post about defining threat, this interaction is a hazard.

These additional risk considerations include the ability to detect a threat before it becomes a hazard or harm actually occurs, and the ability of an organization to correct the harm caused by a specific threat or hazard.

Evaluating Detectability

Threat detection is the likelihood of discovering and correcting a threat before it intersects with operations and becomes a hazard. For example, if an organization has facilities located in a known flood zone, there are several options to increase the detection of flooding before it negatively impacts operations. They can monitor weather forecasts, or interface with local flood sensor networks to provide warning of rising water levels. Through the same consideration, if there was not a flood detection sensor system in the area, then the detection value for the organization would be lower, resulting in a smaller value towards managing vulnerability and not providing as much value in reducing the risk score.

A detection value can be used as a modifier for the probability measure, with moderate detectability having a neutral value and not affecting the risk score. Values above and below refer to poor and good threat detectability, respectively.

| Score | Level of Detectability | Description |

| Almost Certain (0.5) | < 100% | Hazard is easily visible / obvious to most people |

| High (0.75) | < 80% | Hazard is visible to most people |

| Moderate (1) | < 50% | Hazard is visible to knowledgeable people |

| Low (2) | < 25% | Hazard is visible to experts / specialists |

| Remote (3) | < 10% | Hazard is not visible without specific investigation |

To continue the earlier example of a risk that was identified as having a high probability (4) and medium vulnerability (3), adding a detectability rating of low (2) will modify the probability from 4 to 8 (4 x 2), resulting in a risk score of 24 (8 x 3). A detectability rating of high (0.75) would reduce the probability value from 4 to 3 (4 x 0.75), resulting in a risk score of 9 (3 x 3).

Evaluating Correctability

Threat correctability is related to the relative ease of mitigating a specific risk. It includes consideration of the feasibility and effort required to minimize associated vulnerabilities. This consists of both technical and economic concerns, i.e.: “can it be done?” and “can you afford to do it?”

This factor allows for the prioritization of threats that can be managed relatively easily, regardless of their degree of importance. The easier the mitigation, the higher the correctability score, which results in a higher risk score and an indication that action should be taken. However, the reverse is not valid. If mitigating the hazard is difficult, the risk score should not be decreased. Additionally, an unacceptable risk should not be tolerated just because corrective actions are impracticable.

| Score | Correctability | Description |

| 4 | Highly Practical | Mitigation can be done very easily and at low cost |

| 2 | Moderately Practical | Mitigation is feasible. The solution requires additional resources but is achievable at an acceptable cost |

| 1 | Impractical | Mitigation cannot be done easily. The solution is not available or needs significant resources at an unacceptable cost |

Once again working from the earlier example of a risk with a probability rating of high (4) and a vulnerability rating of medium (3), adding a correctability factor of moderately practical (2) will modify the vulnerability score to 8 (4 x 2 = very high). That score is elevated not because the vulnerability is increased, but to artificially raise the priority of mitigation efforts because they are feasible.

While a combination of probability and vulnerability is commonly used to assess risk, it can be useful to consider additional factors that may also impact the determination if a risk is acceptable to an organization. For increasing risk scores for higher probability and vulnerability, a high detectability should be scaled to decrease the risk score, giving a more acceptable risk. A higher correctability should increase the risk score, demonstrating higher risk, and highlighting the need to implement mitigation procedures.

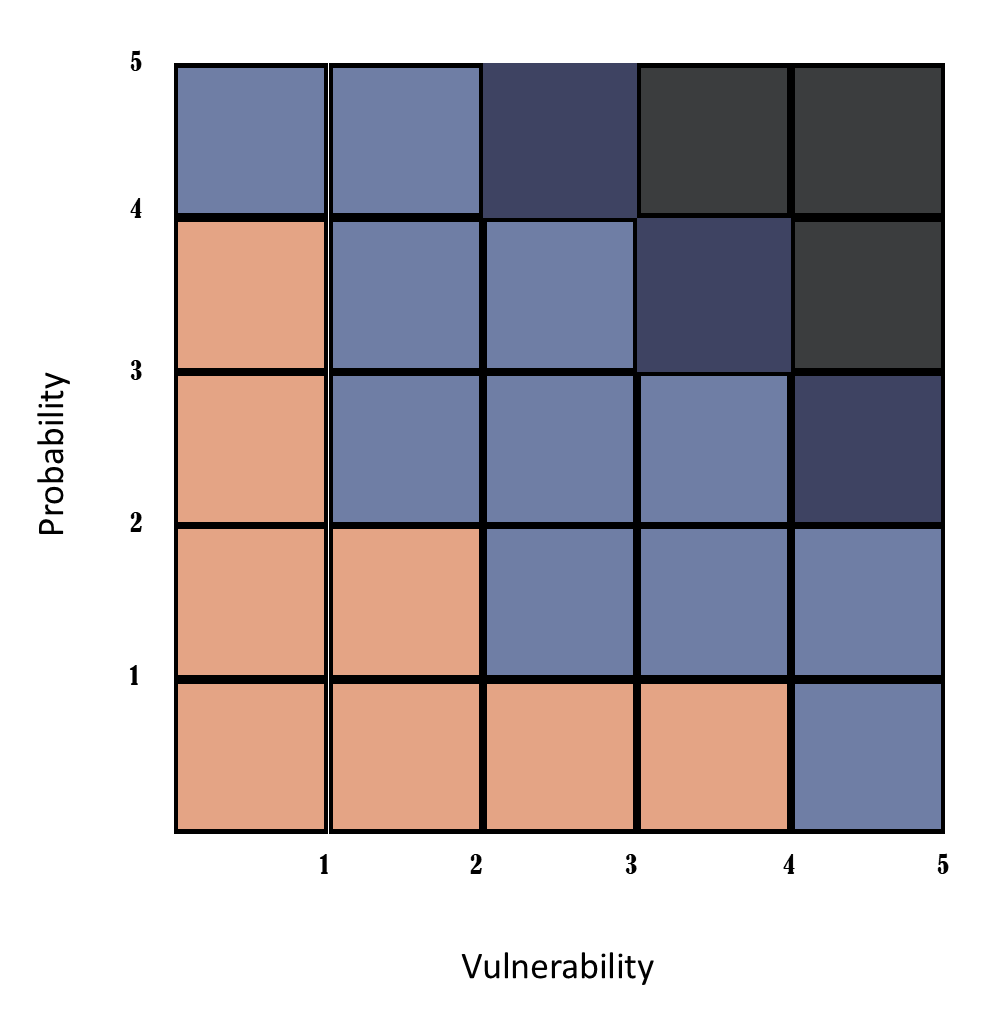

Visualizing Risk

Numbers are just numbers, but a colorful picture can capture the attention of an audience faster than almost any other approach. Visualization of your risk scores will help stakeholders understand risk on a more intuitive level. It allows people to see relationships between the various threats presented, making connections, and identifying patterns in the data which they otherwise may not have been able to.

Risk analysis information has traditionally been presented in a two-dimensional matrix, with probability and vulnerability as the axes.

Using a five-point scale allows for the clear charting of unmodified risk scores. Applying modifiers for detectability or correctability will require you to expand your matrix to support a larger scale. I also recommend including at least half-point indicators for increased fidelity.

Threat assessment and risk analysis are challenging disciplines that are best addressed through the use of a team of individuals to determine the scope, intensity, and possible consequences associated with an identified threat. To support the mitigation of that threat, an organization must decide if the threat is valid by assessing the potential impact of the threat, the probability of the associated hazards, and the organization’s vulnerability to those hazards. While there is no one-size-fits-all approach to this process, it should be holistic and focused on providing information and recommendations to manage the threat effectively and efficiently.

Read the other parts of this 5-part series on developing your Threat Management Program:

Part 1: Defining and Categorizing Threats for your Organization

Part 2: Designing the Ability to Properly Detect a Threat

Part 4: Best Practices for Threat Management

Part 5: Building Your Threat Management Program

Aaron Marks is a Senior Principal with Dynamis, Inc. where he supports clients across the domestic National and Homeland Security communities and international public safety enterprise. He provides operational and subject matter expertise in intelligence analysis and targeting, disaster preparedness, crisis and incident management, and continuity of operations for healthcare related concerns. Aaron has provided in-depth review, assessment, and analysis for technology, policy, and operational programs impacting all levels of government. He is a recognized authority on the application of nontraditional techniques and methodologies to meet the unique requirements of training, evaluation, and analytic games and exercise for the National and Homeland Security communities.

Prior to joining Dynamis, Aaron was the Director of Operations for a commercial ambulance and Emergency Medical Services (EMS) provider in western New York State where he participated in the integration of commercial EMS and medical transportation resources into the local Trauma System. During his 30-year career Aaron has worked in almost every aspect of EMS except fleet services. This includes experience in Hazardous Materials and Tactical Medicine, provision of prehospital care in urban, suburban, rural, and frontier environments, and acting as a team leader for both ground and aeromedical Critical Care Transport Teams.

Aaron is a Master Exercise Practitioner and received a B.A. in Psychology from Texas Tech University in Lubbock, Texas and a master’s degree in Public Administration with a focus in Emergency Management from Jacksonville State University in Jacksonville, Alabama. He is also a Nationally Registered Paramedic and currently practices as an Assistant Chief with the Amissville Volunteer Fire and Rescue Department, Amissville Virginia.